The Kesavananda Bharati case, formally known as His Holiness Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973) 4 SCC 225, is one of the most significant and far-reaching judgments in the history of Indian constitutional law. This landmark case established the ‘Basic Structure’ doctrine, which has since become a fundamental principle in safeguarding the integrity of the Indian Constitution. The case arose from a challenge to the constitutional amendments made by Parliament that threatened the rights to property and religious freedom, as well as the broader question of the limits of Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution. The Supreme Court’s ruling in Kesavananda Bharati not only redefined the balance between the Parliament and the judiciary but also ensured that certain foundational principles of the Constitution would remain inviolable. This case study explores the intricate details of the Kesavananda Bharati case, its historical context, the arguments presented, and its enduring impact on Indian constitutional law.

Background and Context of the Kesavananda Bharati Case

The Kesavananda Bharati case emerged during a period of intense political and constitutional turbulence in India. In the years following independence, the Indian Parliament sought to address socio-economic inequalities through various legislative measures, including land reform laws and amendments to the Constitution. However, these measures often collided with the fundamental rights enshrined in the Constitution, particularly the right to property. The tension between the need for social justice and the protection of individual rights reached a boiling point when the Kerala government enacted the Kerala Land Reforms Act, which aimed to redistribute land and diminish the influence of religious institutions like the Edneer Mutt, led by Swami Kesavananda Bharati.

Swami Kesavananda Bharati challenged the constitutional validity of these land reforms, arguing that they violated his fundamental rights, including the right to manage religious property. This challenge brought to the forefront the broader constitutional question: To what extent could Parliament amend the Constitution, particularly when such amendments threatened the fundamental rights of citizens? The case eventually escalated to the Supreme Court, where it was heard by a full bench of 13 judges, the largest ever in the history of the Court. The outcome of this case would redefine the relationship between Parliament’s amending power and the judiciary’s role in preserving the Constitution’s core principles.

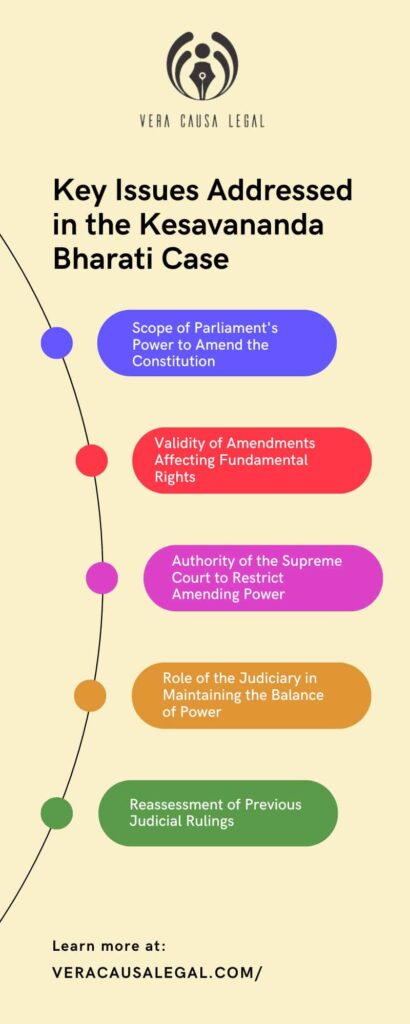

Key Issues Addressed in the Kesavananda Bharati Case

1. Scope of Parliament’s Power to Amend the Constitution

- The primary issue revolved around whether Parliament possessed unlimited authority to amend the Constitution under Article 368 or if there were inherent limitations that safeguarded the basic structure of the Constitution.

2. Validity of Amendments Affecting Fundamental Rights

- The case questioned whether amendments that curtailed or completely took away fundamental rights, such as the right to property and the right to manage religious institutions, could be validly enacted by Parliament.

3. Authority of the Supreme Court to Restrict Amending Power

- A critical issue was whether the Supreme Court had the power to impose restrictions on Parliament’s ability to amend the Constitution, ensuring the protection of certain inviolable elements.

4. Role of the Judiciary in Maintaining the Balance of Power

- The case explored the role of the judiciary in maintaining the balance of power between the legislative and judicial branches, emphasizing that no branch should override the fundamental principles of the Constitution.

5. Reassessment of Previous Judicial Rulings

- The case also questioned whether earlier rulings, particularly in the Golaknath case, should continue to guide the interpretation of Parliament’s amending powers, or if a new judicial approach was required to address the changing socio-political context of India.

Arguments Presented by the Petitioners

1. Protection of Fundamental Rights

- The petitioners argued against constitutional amendments that threatened fundamental rights, particularly the right to property and the right to manage religious institutions.

- They contended that these rights were integral to the freedom and autonomy of individuals and religious entities.

2. Limits on Parliament’s Amending Power

- The petitioners asserted that Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution under Article 368 should not extend to curtailing fundamental rights.

- They claimed that such amendments were an overreach of Parliament’s authority.

3. The Constitution as a Social Contract

- The petitioners emphasized that the Constitution is not just a legal document but a social contract that embodies core principles such as justice, liberty, and equality.

- They argued that these principles form the “basic structure” of the Constitution, which cannot be amended by Parliament.

4. Framers’ Intent and Democratic Values

- The petitioners highlighted that the framers of the Constitution did not intend for Parliament to have unchecked power to amend fundamental rights.

- They argued that allowing Parliament such power would undermine democracy and the rule of law.

5. Judicial Duty to Protect the Constitution

- The petitioners called on the judiciary to protect the Constitution from potential legislative overreach.

- They argued that the Court must impose limits on Parliament’s amending power to preserve the Constitution’s foundational values.

| Argument | Details |

| Protection of Fundamental Rights | Argued against amendments that threatened rights like property and religious autonomy. |

| Limits on Parliament’s Amending Power | Claimed that Parliament’s power under Article 368 should not extend to curtailing fundamental rights. |

| The Constitution as a Social Contract | Emphasized the Constitution as a social contract embodying justice, liberty, and equality. |

| Framers’ Intent and Democratic Values | Argued that unchecked amending power would undermine democracy and the rule of law. |

| Judicial Duty to Protect the Constitution | Called on the judiciary to impose limits on Parliament’s power to preserve the Constitution’s foundational values. |

Arguments Presented by the Respondents

1. Broad Amending Power Under Article 368

- The respondents argued that Article 368 grants Parliament broad and virtually unrestricted authority to amend any part of the Constitution, including provisions relating to fundamental rights.

2. Necessity for Societal Progress

- They emphasized that the ability to amend the Constitution was crucial for addressing socio-economic inequalities and implementing land reforms necessary for social justice.

3. Flexibility of the Constitution

- The respondents contended that the Constitution, as a living document, must be flexible enough to evolve with the times.

- They argued that Parliament, as the representative body of the people, should have the ultimate authority to determine the nature and extent of amendments.

4. Protection of the Democratic Process

- They asserted that placing restrictions on Parliament’s amending power would undermine the democratic process and limit the legislature’s ability to enact laws that reflect the will of the people.

5. Rejection of the “Basic Structure” Doctrine

- The respondents argued that the concept of a “basic structure” was not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution.

- They maintained that introducing such a doctrine would amount to judicial overreach, allowing the judiciary to overrule the will of the people as expressed through their elected representatives.

6. Framers’ Intent for Constitutional Flexibility

- The respondents argued that the Constitution’s framers intended for Parliament to have the flexibility to make necessary amendments for the nation’s growth and development without being constrained by judicial doctrines.

| Argument | Details |

| Broad Amending Power Under Article 368 | Argued that Article 368 grants Parliament unrestricted authority to amend any part of the Constitution. |

| Necessity for Societal Progress | Emphasized that constitutional amendments are crucial for addressing inequalities and land reforms. |

| Flexibility of the Constitution | Contended that the Constitution must be flexible to evolve, with Parliament having ultimate authority over amendments. |

| Protection of the Democratic Process | Asserted that restricting Parliament’s amending power would undermine democracy and limit legislative actions. |

| Rejection of the “Basic Structure” Doctrine | Argued that the “basic structure” concept is not in the Constitution and that introducing it would lead to judicial overreach. |

| Framers’ Intent for Constitutional Flexibility | Maintained that the framers intended for Parliament to have the flexibility to amend the Constitution for national growth. |

Judgment of the Supreme Court in the Kesavananda Bharati Case

The Supreme Court’s judgment in the Kesavananda Bharati case is one of the most consequential decisions in Indian legal history, fundamentally shaping the trajectory of constitutional law in the country. Delivered by a 7-6 majority, the Court held that while Parliament does indeed have the power to amend the Constitution under Article 368, this power is not absolute. The Court introduced the now-famous “Basic Structure” doctrine, which stipulates that certain essential features of the Constitution—referred to as its “basic structure”—cannot be altered or destroyed by any amendment.

The majority opinion, led by Chief Justice S.M. Sikri, identified key elements that constitute the basic structure of the Constitution, including the supremacy of the Constitution, the rule of law, the separation of powers, the independence of the judiciary, and the protection of fundamental rights. The Court asserted that these elements are so fundamental to the Constitution’s identity that any amendment seeking to alter them would be unconstitutional, even if passed by the requisite majority in Parliament.

The judgment also introduced the concept of judicial review over constitutional amendments, empowering the judiciary to strike down any amendment that threatens to damage or destroy the basic structure of the Constitution. This ruling effectively placed a check on Parliament’s amending power, ensuring that the core principles of the Constitution would remain inviolable.

The Kesavananda Bharati judgment was a landmark moment in Indian jurisprudence, marking the balance between parliamentary sovereignty and judicial supremacy. It underscored the idea that while the Constitution is a living document, its foundational principles must be preserved to maintain the integrity and identity of the nation.

Significance of the Basic Structure Doctrine

The Basic Structure doctrine, as established in the Kesavananda Bharati case, is one of the most significant contributions to constitutional law, not only in India but globally. This doctrine fundamentally reshaped the balance of power between the legislature and the judiciary, ensuring that certain core principles of the Constitution remain beyond the reach of parliamentary amendments.

The significance of the Basic Structure doctrine lies in its ability to safeguard the Constitution from potential abuse of power by the legislature. It ensures that while Parliament has the authority to amend the Constitution to reflect the changing needs of society, it cannot alter the Constitution’s core values, such as the rule of law, the separation of powers, the independence of the judiciary, and the protection of fundamental rights. These principles form the bedrock of India’s democratic framework and are essential to preserving the nation’s constitutional identity.

Furthermore, the doctrine empowers the judiciary to act as a guardian of the Constitution, allowing it to strike down any constitutional amendments that threaten to undermine the basic structure. This judicial oversight serves as a vital check on the amending powers of Parliament, preventing any single branch of government from accumulating excessive power or altering the Constitution’s essential character.

The Basic Structure doctrine has also influenced constitutional jurisprudence in other countries, with courts in various jurisdictions citing it as a precedent when dealing with constitutional amendments. It represents a profound recognition that a constitution is more than just a legal document—it is a living embodiment of a nation’s core values and principles, which must be protected and upheld for the sake of future generations.

In summary, the Basic Structure doctrine ensures that while the Constitution can evolve, its fundamental ethos remains intact, thereby preserving the stability and continuity of the Indian democratic system.

Impact of the Kesavananda Bharati Case on Indian Constitutional Law

| Impact | Details |

| Introduction of the Basic Structure Doctrine | The Supreme Court introduced the Basic Structure doctrine, ensuring protection of the Constitution’s fundamental principles against potential legislative overreach. |

| Judicial Review and Supremacy | The ruling empowered the judiciary to review and invalidate amendments that violate the Constitution’s basic structure, reinforcing judicial supremacy in constitutional matters. |

| Balanced Power Distribution | The case led to a more balanced distribution of power among the branches of government, preventing any one branch from becoming too dominant. |

| Precedent for Future Constitutional Amendments | The case set a precedent for the scrutiny of future amendments, with the Basic Structure doctrine being used in landmark cases like Minerva Mills and Indira Gandhi’s Election case. |

| Global Influence | The doctrine inspired constitutional courts in other countries to adopt similar principles, recognizing that certain fundamental aspects of a constitution should remain immutable. |

| Enduring Impact on Indian Constitutional Law | The case remains a cornerstone of Indian constitutional jurisprudence, ensuring the protection of the Constitution’s essential character and fundamental principles. |

The Kesavananda Bharati case had a profound and lasting impact on Indian constitutional law by introducing the Basic Structure doctrine. This doctrine serves as a safeguard against potential legislative overreach, ensuring that the fundamental principles of the Constitution remain protected. The ruling established a clear distinction between Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution and the judiciary’s role in preserving its core values, thereby reinforcing the concept of judicial supremacy.

One of the significant outcomes of the case was the balanced distribution of power among the branches of government, preventing any one branch from becoming overly dominant. The case also set a crucial precedent for the scrutiny of future constitutional amendments, as seen in the Minerva Mills and Indira Gandhi Election cases, where the Basic Structure doctrine was invoked to protect judicial review and the democratic process.

Moreover, the influence of the Kesavananda Bharati case extends beyond India’s borders, as the Basic Structure doctrine has inspired constitutional courts in other countries to adopt similar principles. Today, the case remains a fundamental part of Indian constitutional law, ensuring that while the Constitution can adapt to changing times, its essential character and principles will always be preserved. This case highlights the importance of judicial vigilance in maintaining the delicate balance between change and continuity in a constitutional democracy.

Subsequent Developments and Relevance Today

The Kesavananda Bharati case remains one of the most influential decisions in Indian constitutional law, with its impact resonating for decades. The Basic Structure doctrine, established through this case, became a critical tool for the judiciary to safeguard the Constitution against potential legislative and executive overreach. This doctrine has been pivotal in landmark cases like Minerva Mills (1980), where the Supreme Court struck down parts of the 42nd Amendment, and the Indira Gandhi Election case (1975), which protected democratic processes from executive dominance.

The doctrine ensures that the foundational values of the Constitution—democracy, secularism, the rule of law, and the protection of fundamental rights—are preserved, making the Constitution a living document. The Kesavananda Bharati case continues to shape constitutional law in India and has influenced courts worldwide, maintaining its relevance in contemporary legal and political discourse.

Conclusion

The Kesavananda Bharati case stands as a monumental judgment in the history of Indian constitutional law, profoundly shaping the relationship between the legislature and the judiciary. Through this case, the introduction of the Basic Structure doctrine has ensured that the core principles of the Constitution—democracy, secularism, the rule of law, the separation of powers, and the protection of fundamental rights—remain inviolable, regardless of the political climate or the composition of Parliament.

This landmark judgment marked a turning point, affirming that while the Constitution is a living document capable of evolving with society, certain foundational values must be preserved to maintain the nation’s integrity and identity. The doctrine has since been a critical judicial tool for protecting these values from potential legislative overreach, maintaining a balance of power among government branches.

The legacy of Kesavananda Bharati extends beyond India, influencing constitutional courts globally. As a cornerstone of constitutional jurisprudence, it ensures the Indian Constitution remains a robust and enduring framework for governance.

At Vera Causa Legal, recognized as the best law firm in Delhi, we are dedicated to upholding these constitutional values, protecting our clients’ fundamental rights, and preserving justice, liberty, and equality for future generations.